Finland didn't forget how to run

and why the USWNT will continue to lose.

When Mira Potkonen won the Bronze medal in the Women’s Lightweight boxing in August 2021, it marked a step forward for Finland at the Olympics. They’d surpassed their medal total achieved five years earlier in Rio de Janeiro despite bringing 16% fewer athletes to the games. Potkonen’s Bronze was only Finland’s second medal of the 2020* Tokyo Olympics.

*for historical record keeping purposes, we really need to ignore branding and label these Olympics by the year they took place, i.e 2021.

This low medal total raised no alarms. Finland are not currently viewed as a sporting powerhouse, their average medal table placing in the last two decades of the Summer Olympics is 66th. As you may know or may have surmised from the telegraphed lede, this wasn’t always the case. Historically, Finland are the 14th most successful Summer Olympics nation. Between 1912-1936, 6 Olympic cycles, their average placement was 4th. Which in real terms puts them in a head to head v Sweden as the 2nd best Olympic nation, behind USA, during this period.

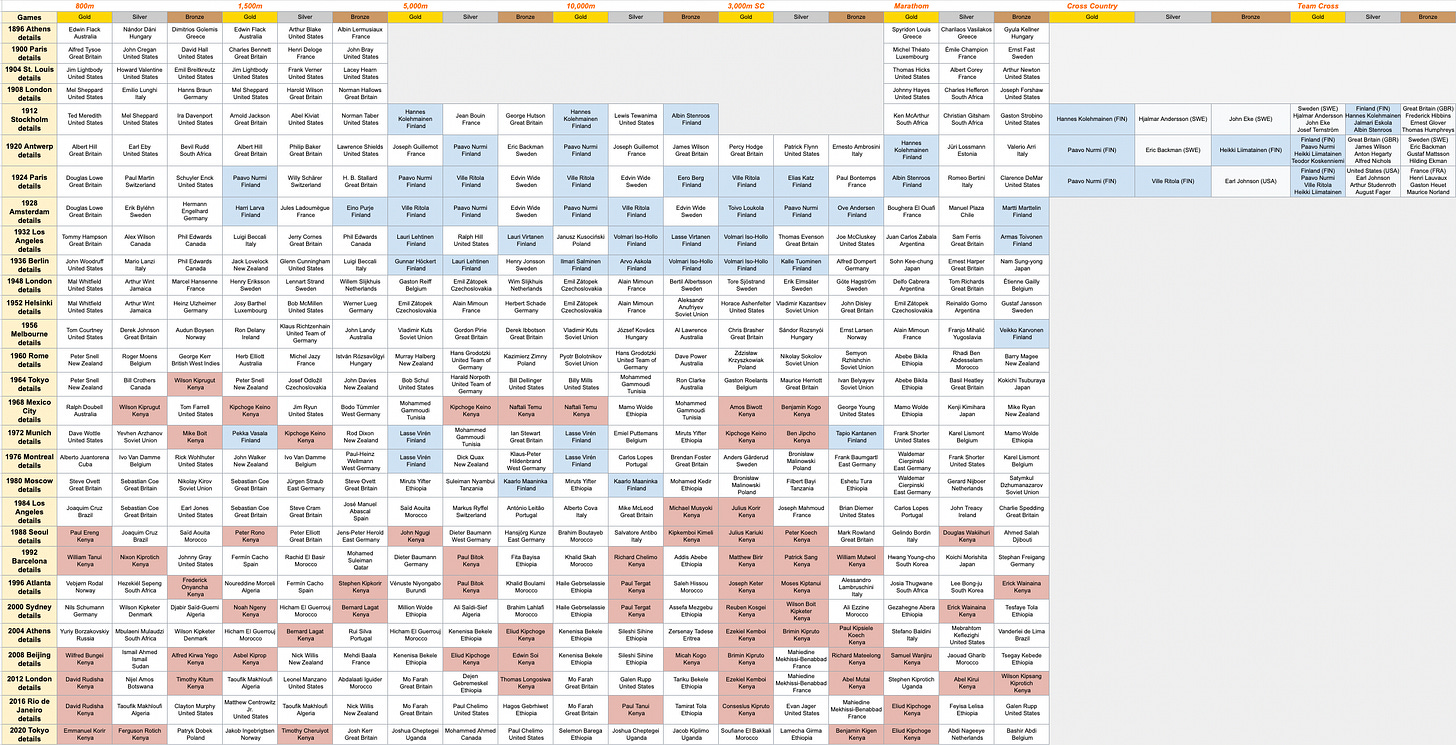

Finnish Olympic success was built on two pillars, Wrestling and Track and Field (T&F). T&F was the crown jewel, 114 of their 304 Olympic medals won, but even more significantly 48 of their 100 Gold Medals. What do these numbers mean without any context? After 29 Summer Olympics and 128 years of Games, they sit apart as one of the big five, above all other nations. Only the United States, Soviet Union and Great Britain have won a greater amount of total or gold T&F medals than Finland, with East Germany trailing just behind. So, why have a historically great T&F nation only won 3 Olympic medals since 1996?

If we jump down to the next link in the chain, Finnish T&F Olympic success was specifically built on two more pillars, Javelin (specifically male javelin) and 800m right through to Cross-Country distance running. The dominance in Javelin (again, important to note male only) is near historically insurmountable. They have won 7 of the 29 possible Gold medals and 22 of the 87 total medals since the Olympics began. For context, the 2nd most successful nation, Soviet Union, have won 7 medals altogether. Even more significantly, this success was not based on the performances of individual outliers, their 7 gold medals were won by 6 different athletes and 17 different Finnish men have won medals in the Javelin altogether. For anyone still not convinced by their dominance, at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, they held an unofficial ‘Two handed Javelin’ test event, in which a throwers score was calculated by combining the distance with their right hand to the distance with their left hand. Finnish athletes won Gold, Silver and Bronze.

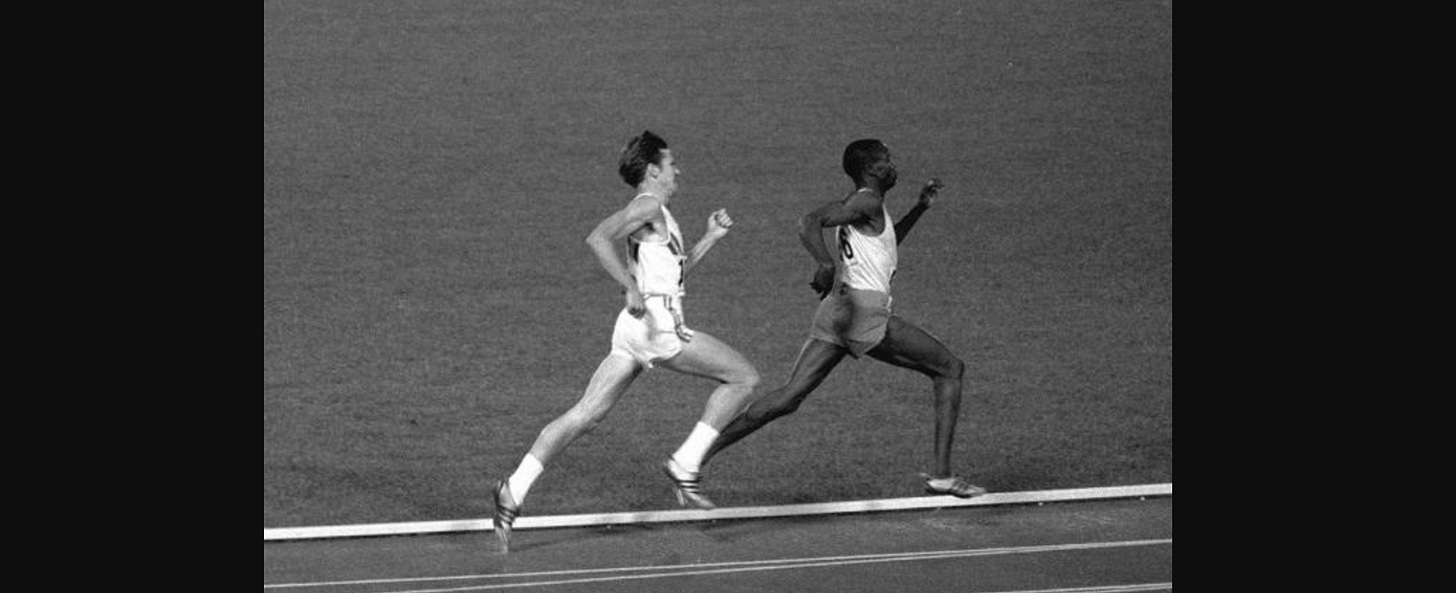

Albeit impressive, their ability to throw did not capture the imagination of the viewing public like their ability to run. 18 gold medals and 36 overall between 1912 and 1936. 5,000m? 5 golds. 10,000m? 5 golds. 3,000m Steeplechase? 4 golds. Marathon? 2 golds. Cross-country? 3 golds in 3 Olympic games until the event was discontinued in 1924, before Finland could continue to rack and stack. Paavo Nurmi (9 golds, 3 silvers) is seen by some as the Greatest Olympian of All-Time, competing in just 3 Olympics before being blackballed from competing in the 1932 Olympics. But Finnish success was not built solely on individuals, over 20 different men medalled in these events - if a running podium didn’t have two ‘Flying Finns’ on it, odds are that you’d just watched a sprint race.

What are three possible explanations for why a country may win less Olympic medals over a certain time period? I’ve explained two above - 1) an event they favour is withdrawn from the schedule or 2) a dominant Athlete is unable to compete. Pretty impactful, but both pale in comparison to 3) what if there was a World War and the Olympics was not held for 12 years. Nurmi’s prodigy Taisto Mäki is not a household name. In the summer of 1939, he broke the world records for the 5,000m and 10,000m. In November 1939, he was deployed on the Karelian Isthmus to fight in ‘The Winter War’.

After WW2, Finnish distance running was never quite the same. Heading into London 1948, Viljo Heino held the 10,000m world record, but due to injury could not compete with the emerging dominance of Czech Athlete Emil Zapotek. Finland left England without a single track medal. Twelve years after they were originally due to host, 1952 finally saw the Olympics come to Helsinki for the first (and only) time. Despite fervent local enthusiasm and the biggest team in Finnish Olympic history (213 more athletes than they’d bring to Tokyo 2021), Finland finished the Games without a T&F gold medal for the first time since 1908.

Success in the 1950s was sporadic at best, but the 1960s were entirely barren, medal-less and unmemorable for Finland on the track. Finnish T&F was declared dead on arrival at the 1968 Mexico Olympics. Enter the 1970s, The Beatles were gone but improbably Finnish distance running was back? Finland finally had their heir to Paavo Nurmi in Lasse Virén. A Policeman who had barely competed Internationally prior to the 1972 Olympics, turned up, won the 10,000m gold in a new World Record and then doubled with the 5,000m gold. Four years later, he repeated the trick before throwing in a 5th place finish in the Marathon for good measure. Kaarlo Maaninka (10,000m silver + 5,000m bronze) carried the team into the 1980 Moscow games and Martti Vainio was the man for 1984 in Los Angeles, coming in off the back of breaking Virén’s 5k record.

In hindsight, the 70s wasn’t the rebirth of Finnish distance running, but a particularly violent death rattle. Maaninka’s 5,000m bronze, the last track medal, the Finns ever picked up. It’s easy to speculate reasons to explain the rise and fall and rise and fall of Finnish running - Sisu (+), lifestyle + cross-country skiing heritage (+), Nurmi’s revolutionary training methods (+), success inspiring success i.e Virén idolised Nurmi (+), rival nations copying training methods i.e Zapotek idolised Nurmi (-), impact of WW2 on male population under 30 (-), socio-economic conditions (+/-) - then the constant elephant in the room with athletics and especially sudden rises and falls in success, doping.

After a silver medal on the opening weekend in the 10,000m, Vainio tested positive for anabolic steroids. Finland awoke early in the morning to watch him race for the 5,000m title, only to be greeted by breaking news that he would not compete and his 10,000m medal would be stripped. Where it gets interesting, is that Vainio was not surprised he failed his test and neither were the Finnish Athletics Federation. In fact, earlier that year, he’d failed an internal test but they’d covered it up for their star athlete. Some suggest that this international embarrassment, not only forced Finland to implement stricter domestic testing (hypothetically driving down times) but also impacted the general publics affection + participation in distance running. Some more cynical, would suggest that Finland’s Athletics Federation were forced to wind down the state sponsored doping ring they were operating themselves.

Vainio’s example is a pretty black and white example of an athlete taking an illegal substance and the system catching them. Maaninka’s post career admissions of ‘blood doping’ for the 1980 Olympics are much hazier. Technically, this was not made illegal by the IOC until 1985, despite them not even knowing how to even test for it at the time. Prior to the invention of EPO in 1985, blood doping was a fairly convoluted process. Extract a litre of blood from the athlete in the lead up to a major competition, with the blood placed in cold storage, the athlete trains and the body restores blood to it’s normal levels. Prior to the race, red cells from the extracted blood are then transfused back into the athlete, increasing the haemoglobin level and ability to carry oxygen to the lungs, resulting in improved aerobic fitness. Now why is this relevant to pre-Maaninka Finnish athletes and understanding the context Finnish distance sport (not just on the track) operated in during the 60s and 70s? In 1971, a Swedish physiologist Bjorn Ekblom released a groundbreaking set of findings from his studies into the effect of bloodletting and transfusions in relation to athletic performance. This was deemed as one of the most revolutionary advancements in the history of sports science. However, the reaction in Finland was fairly muted compared to the rest of the world and can be summed up as “yeah guys, we’ve known that for years.” In reality, it wasn’t until the ‘rebirth’ of Finnish athletics in the early 70s and subsequent suspicion about their methods from foreign athletes, that they became sheepish about discussing practices they’d been partaking in prior to them officially being invented.

I finished with doping, but doping does not explain Finland’s athletic history. Even the most cynical, of which I am one, would have to accept that doping, is just the extreme end point of a myriad of (cultural, socio-economic, historical etc etc) variables that leads a country to place value on performance in the first place. The majority of variables that impact a countries chances of winning an Olympic medal in a certain event are external, the most obvious of these is the Cedric Daniels principle - “you can not win, if you do not play.”

As covered earlier, Finland are the 3rd most successful, still active, T&F nation in Olympic history. Kenya will overtake them and move into 3rd place for total medals during the Paris Olympics next summer, i’ll guess that they’ll do it with a final weekend medal in the women’s marathon. Kenya will overturn Finland’s 14 gold medal lead too - a date on that less certain, but it’ll probably happen in the 2030s. Like the Finns, Kenya’s T&F success is built on events from 800m through to the marathon and if you really want to stretch the link between the two nations, Kenya’s sole field medal was achieved by Julius Yego in the Javelin.

In November, Kenya’s first ever Olympic medalist sadly passed away at the age of 84. Wilson Kiprugut’s 800m bronze at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics was their sole medal that year, in only the nations 3rd Olympics. The first man to win an Olympic T&F medal for Finland, died at the age of 70 in 1941.

Like all nations, Kenya’s sporting journey is inextricably interconnected to every other event in their history. Kenya’s Olympic history is a particularly interesting proxy with which to show some of these connections. The first Olympics was held in 1896 and one of the founding nations was Great Britain. Kenya was occupied by Britain’s colonial rule from 1895 until their independence was achieved in 1963. It was only in 1955 that the British allowed the creation of the Kenyan Olympic committee and they entered the first two Olympics under the title ‘The Colony and Protectorate of Kenya.’ In reality these first two Kenyan Olympic teams, were mainly made up of British Ex-pats or Kenyan Sikh’s, who occupied a higher caste status than Black Kenyans. Kenya’s status as an ever present Field Hockey qualifier between 1956-1988, is a perfect example of the impact of immigration and demographic change on the sporting preferences of a country. Coincidental or not, that a black Kenyan in Kiprigut, was their first Olympic medalist a year after independence, feels fitting.

Remember Finland’s distance running renaissance in the 1970s? Kenya built on 1964 with 14 track medals from the 1968 + 1972 Olympics, establishing themselves as an emerging force in the sport, especially in any race between 800m-3000m. However, they’d be the last Olympic medals Kenya won until 1984. The 1976 Montreal Games, saw a 29 country (Kenya among the majority African cohort) boycott in protest of the IOC’s refusal to ban New Zealand, who had defied the United Nations call for a sporting embargo, by playing rugby in apartheid South Africa. In similar fashion, Kenya were part of an even bigger boycott of the 1980 Moscow game, a US lead move by 60+ countries at the height of the New Cold War and Russian military advancements in Asia. Considering the hierarchy of the sport at the time and in every Olympics since, Lasse Viren not having to compete against any African distance runner in 1976, probably lead to the lowest relative field quality in the distance events history.

Including Kiprugut’s bronze, Kenya have won 5 medals in events in the 400m variants, one aforementioned javelin medal and an additional 7 boxing medals. The 100 remaining medals won, were in events in running events from 800m (> 1500m > 3000m steeplechase > 5000m > 10000m) to the marathon. Quick maths, across the 13 Olympics they’ve competed in as an independent nation, they’ve picked up just over 7.5 medals per Olympics in these 6 events. While it’s hard to ever pick out individual medals that Kenya gained from Finland directly, it’s undeniable that the rise of one, can lead to a perceived (or real medal) decline in another. The worst case scenario of this is if perceived decline becomes real decline, if public interest fades and participation:funding dries up or is focused on sports that offer a great chance of elite success.

The point here, isn’t really about the history of Finland or Kenya specifically (the last 5 paragraphs could be written about Ethiopia with slight alterations or even Germany sprinting v Jamaica), but to illustrate how the dominant nations in sport can change, how quickly this change can happen, and cover a few variables that could effect this change. Truly global sport is still a very young project, many would argue an incomplete project and one masquerading as a meritocracy, so further change is inevitable. Earlier, I predicted that Kenya will become the 3rd most successful T&F nation sometime in the 2030s - the best counter to this isn’t a Kenyan implosion, or even their closest trailers Jamaica catching them up, but that they suffer in the same way Finland did with an emerging East African nation eating into their medal share. Since 2017, Uganda have emerged as a genuine challenger in the distance events on the global stage, already producing some of the greatest athletes of all time, picking up Olympic + World Championship medals along the way. Will they be ‘1970s Finland’ or sustain it like ‘1960s Kenya’, likely they’ll split the difference, before the emergence of the next great distance running nation divides the share of the pie even further.

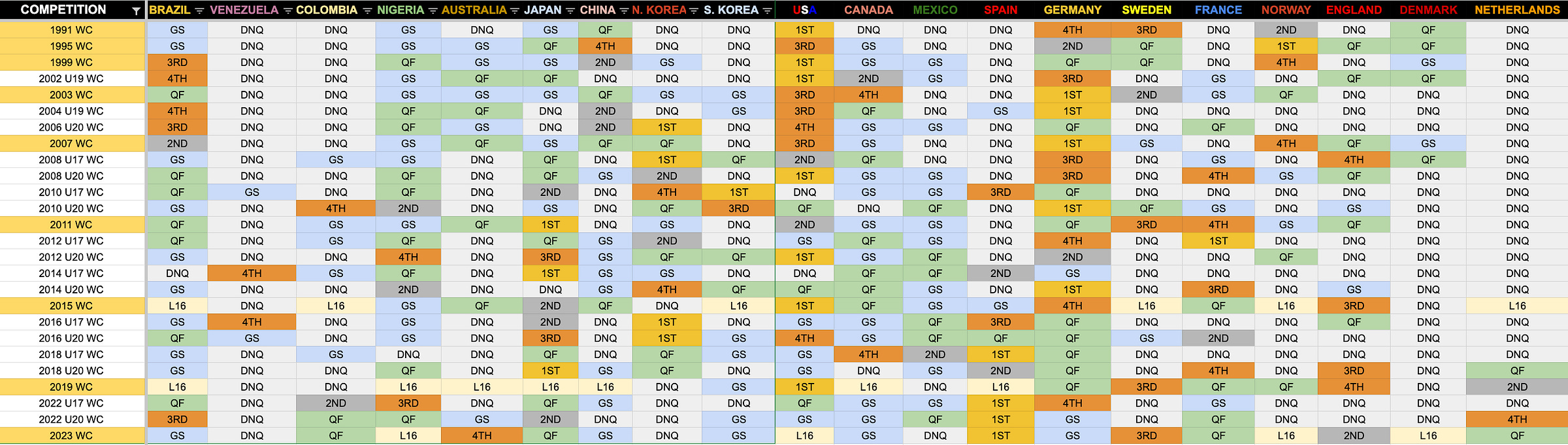

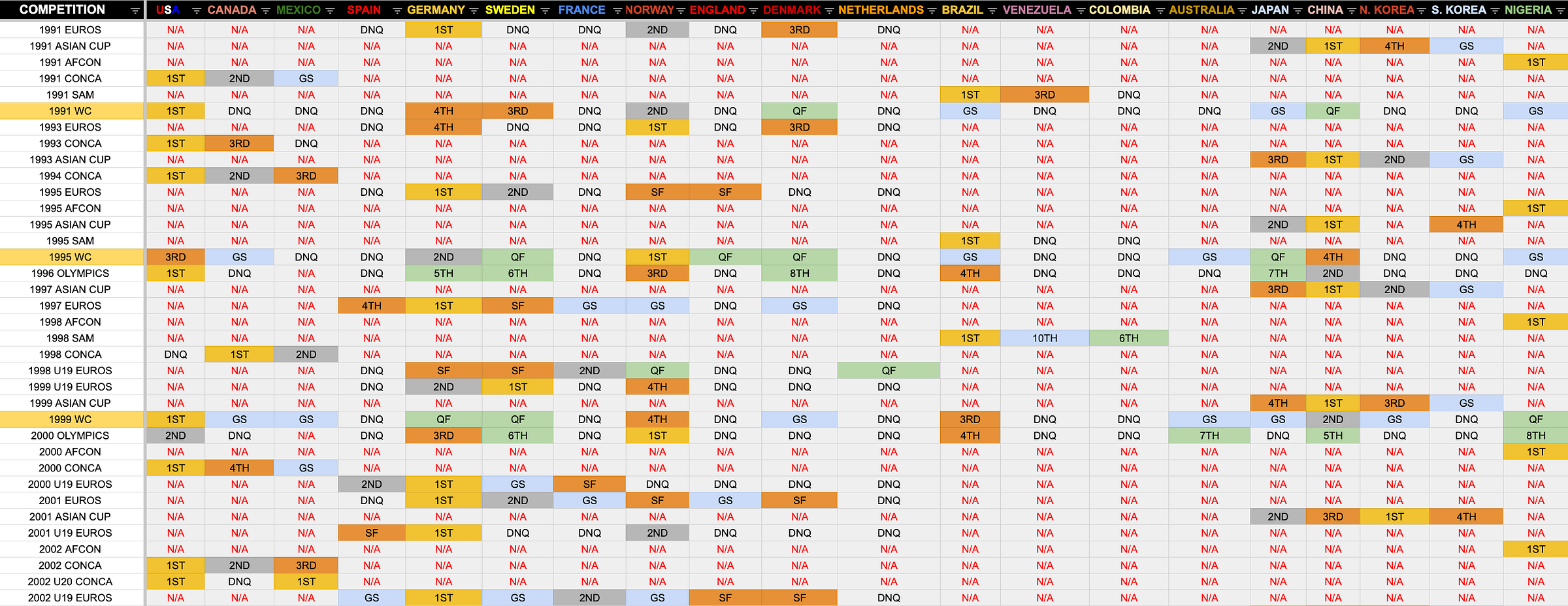

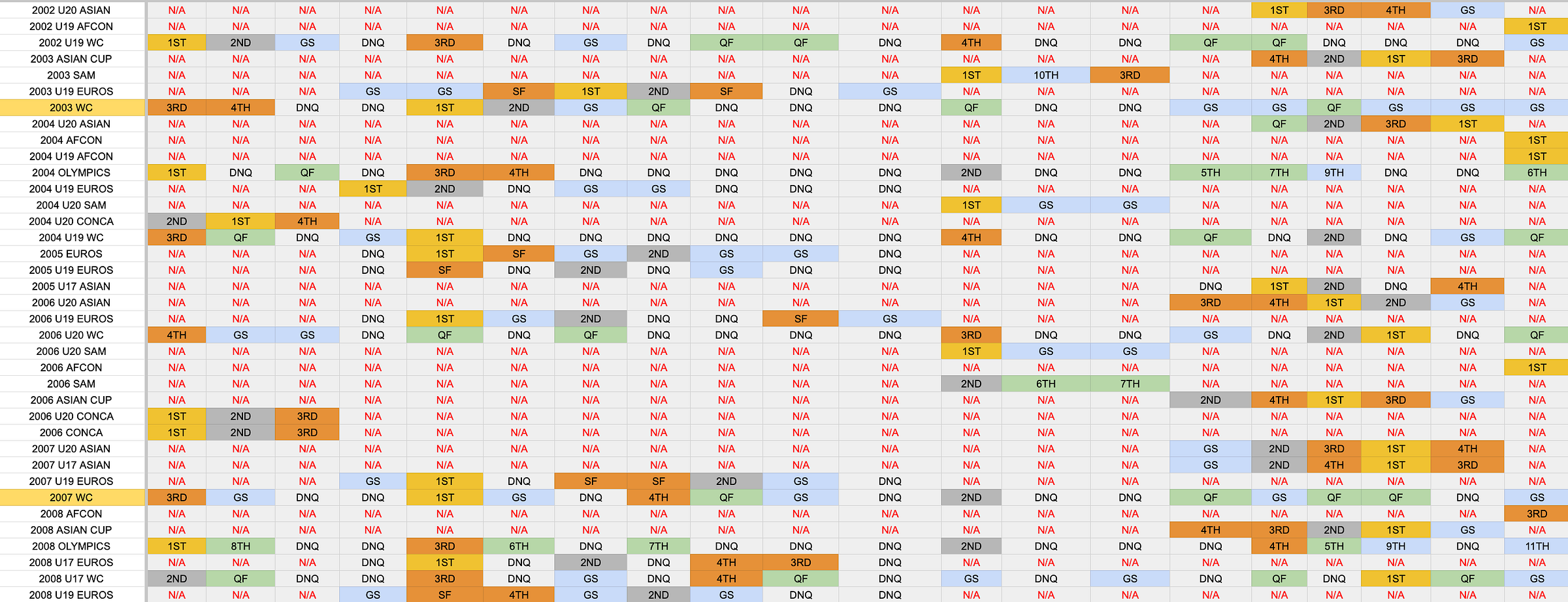

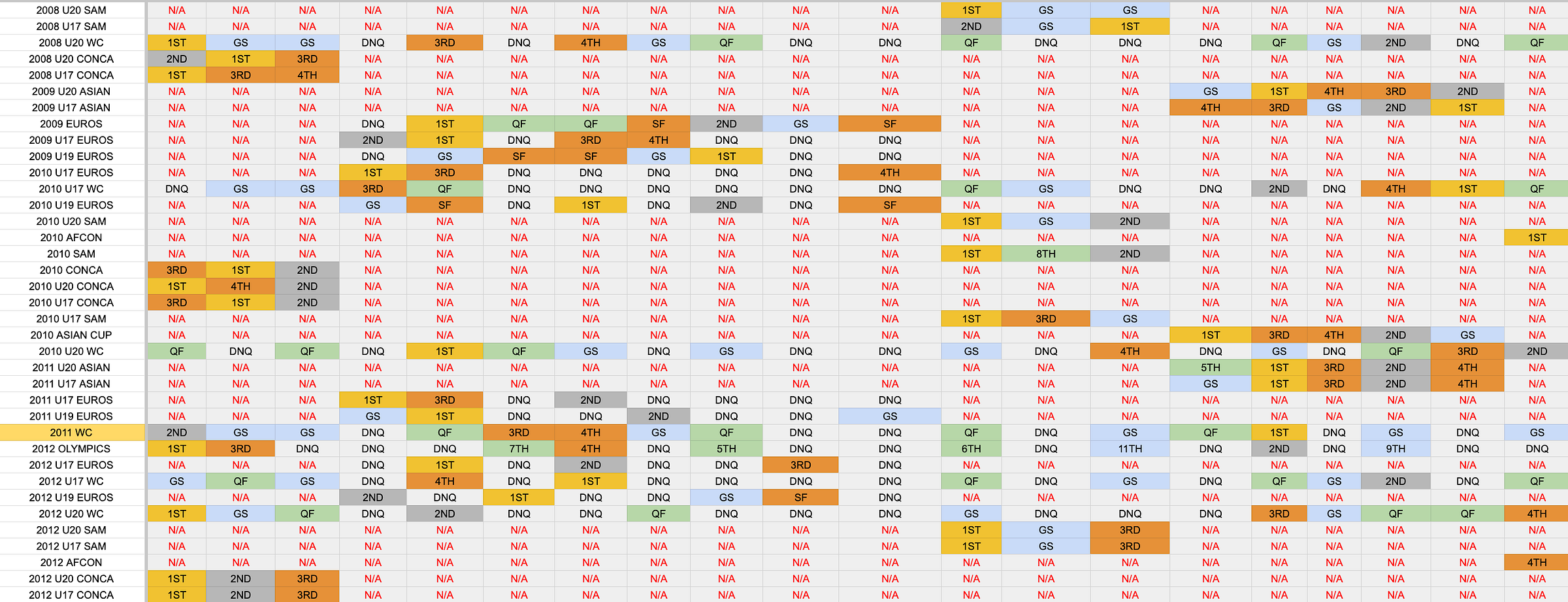

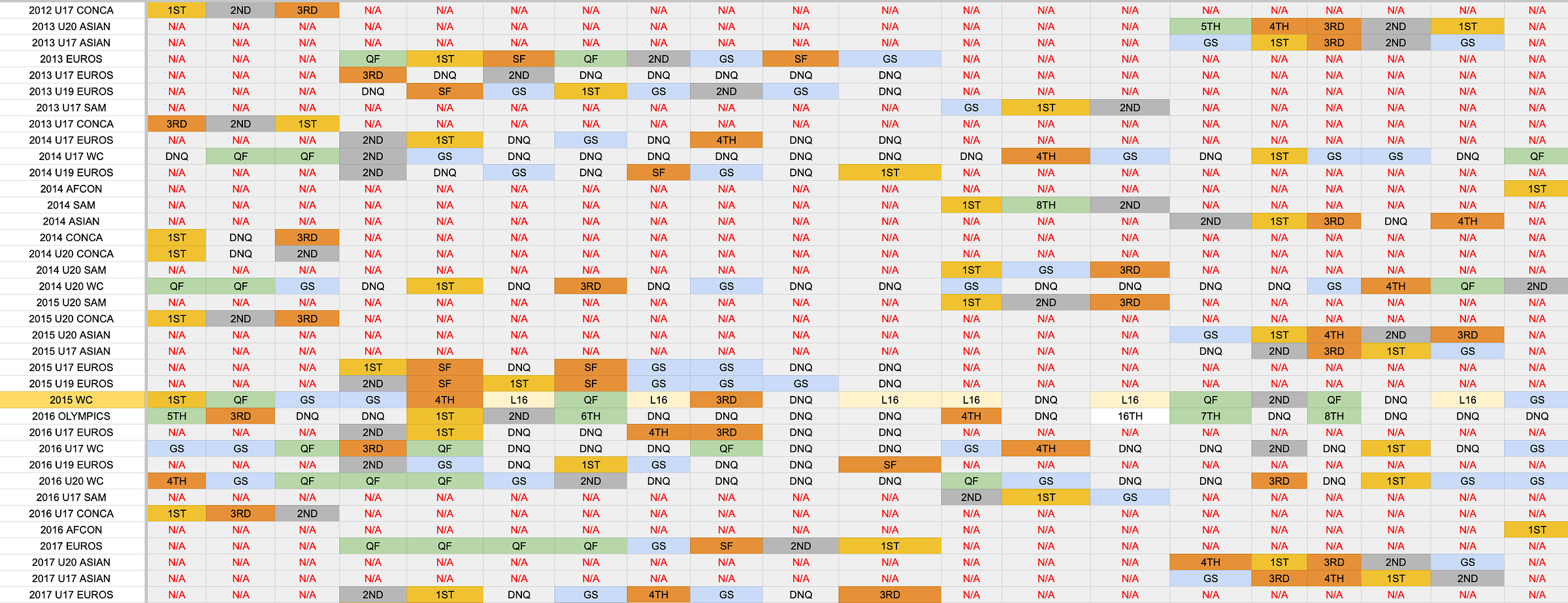

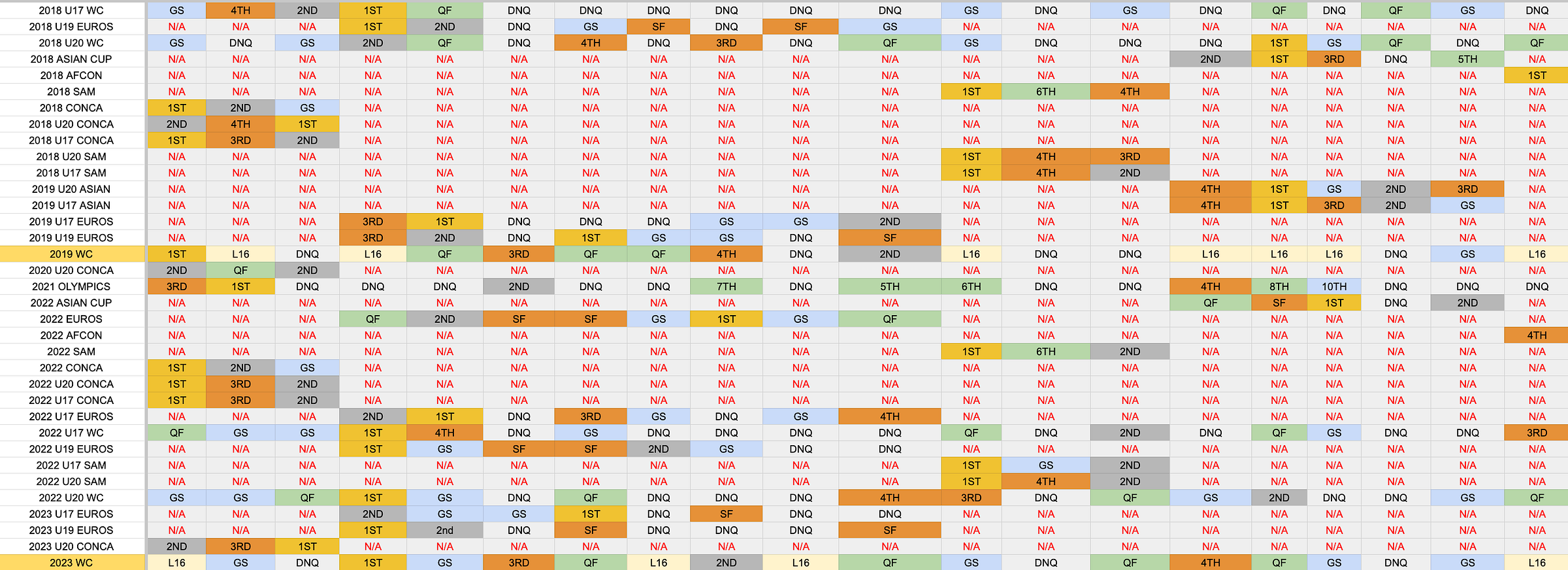

Women’s International football on a global scale essentially began in 1991, with the inaugural World Cup preceded by continental championships taking place on all 6 inhabited continents for the first time. Take up of the sport for the first 20 years, was slow and essentially lead to US + Germany fighting for dominance, with a sprinkling of competitiveness from China, Scandinavian nations, Brazil and Japan. The beauty of living through the development of a young modern sport, is that the speed of change can be frighteningly quick and you can witness it in real time.

Some people will claim that youth tournament results mean everything. Some will claim they mean nothing. The reality probably lays somewhere in the middle - they don’t mean everything, but they definitely mean something. Some ways to attempt to figure out what they mean, is to look for long term trends, to track individual player transition to senior competition, to identify outlier cohorts v a sustained depth of talent, and to watch the games to figure out why teams are actually winning.

Often, the first question to ask is - are the 20-23 players in the squad even the best 20-23 in the age group at this given moment? The correlation between youth success and senior success is fairly strong in men’s football, but a problem when analysing men’s football, is the sheer size of the player pools involved. Not only may the U17 team you are watching not contain the best XI of players projecting forward, but quite often, they do not even field the best U17s at the time. The economic power of club football can impact national selection or put pressure on players to drop out to fulfil club responsibilities, but the economic power of mens football can also sustain the larger players pools through the developmental stage and reduce the amount of complete dropouts - with more ledges to be caught on as they drop down the system, with an opportunity to then rise back up. Women’s football operates more like other elite sports, less players go into the elite development pathway overall, but players can stay in that pathway for longer, as there are less sources to pick replacements from. Therefore, the players you’re seeing in youth tournaments are more likely to be the players you’re seeing in senior tournaments, for better or worse.

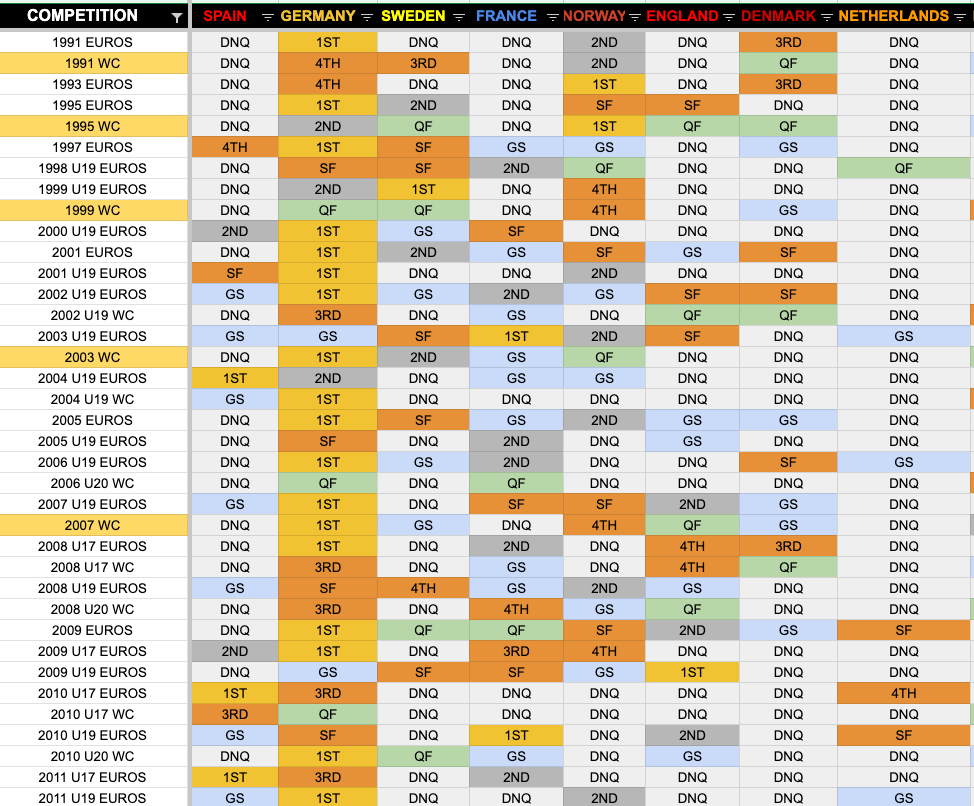

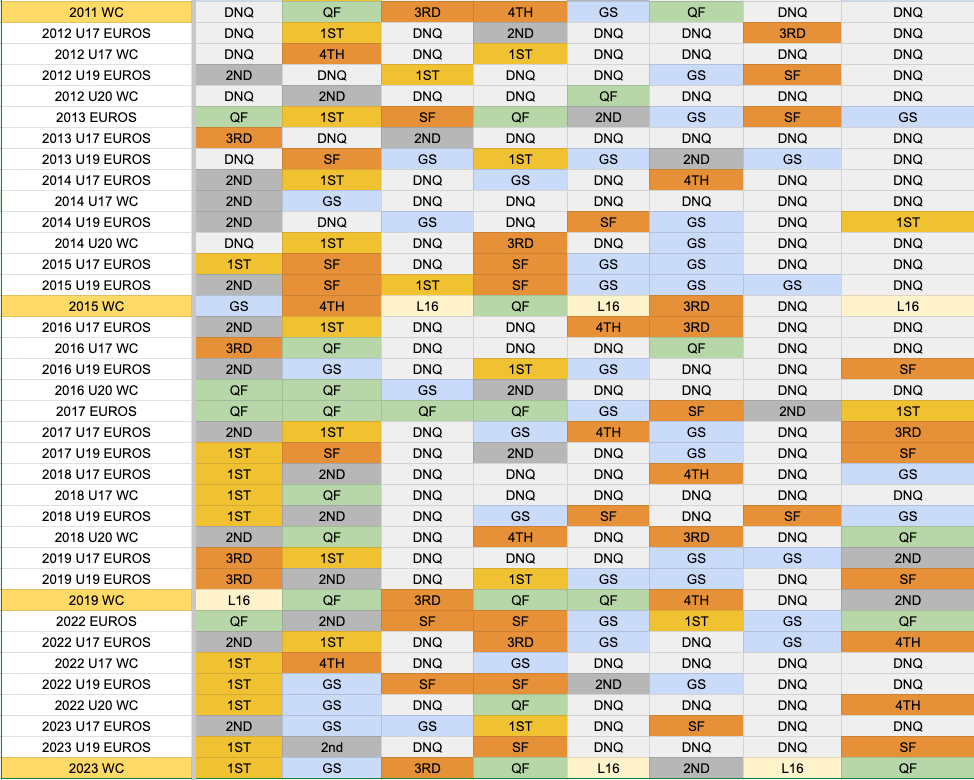

Spain were something of an irrelevance on the global or continental stage, for the first 18 years of the sport. Germany were established as the dominant European side, in 30 G+C (Global+Continental) tournaments, they progressed to the semi-final stage 27 times overall, going on to winning 16 tournaments outright. In an apparent aberration, Spain made their way through to the 2009 U17 Euros final, giving themselves the chance to cause an upset v Germany. They lost 7-0. However, the next year, Spain returned and won the tournament, courtesy of a squad featuring future two time Ballon d'Or Féminin winner Alexia Putellas playing up an age group. This qualified them for the 2010 U17 World Cup, Spain’s first Women’s World Cup at any age level, where they finished 3rd. In 2011, many of this group were eligible to play and win the U17 Euros again and then in 2012, having finally made the step up to U19s, this 93+94 born cohort missed out on completing the youth Euros double in a final defeat against a Sweden side featuring many now familiar names (Elin Rubensson, Magdalena Eriksson, Fridolina Rolfo, Lina Hurtig, Joanna Andersson, Amanda Ilestedt). This was established as a talented cohort in isolation, but was it anything more?

In the 26 G+C youth tournaments since 2012, Spain have been semi-finalists 23 times, finalists 19 times and winners 9 times. Forget overhauling Germany, with the field more competitive than it’s ever been, Spain have overhauled everyone, including the USA.

Aitana Bonmati is going to become the 2nd Spanish winner (and 3rd in a row) of the Ballon d’Or Feminin when it’s announced next month. She played in 6 G+C youth tournaments and made the final in all 6. Last month she was a member of the senior World Cup winning team, winning the Golden Ball. It’s important to note here that for many, the 2nd best team at the 2023 Women’s World Cup, was Japan. Japan played Spain in the Group Stages, winning 4-0. Despite reaching every final, Bonmati’s Spanish youth teams didn’t win them all. In the 2014 U17 World Cup final, they lost to Japan and in the 2018 U20 World Cup final….they lost to Japan. The story of the 2023 World Cup was almost the story of the 2018 U20 WC - Japan (featuring Hinata Miyazawa, Moeka Minami, Fuka Nagano, Riko Ueki, Hana Takahashi, Jun Endo, Honoka Hayashi + Saori Takarada) beat England (feat Chloe Kelly, Lauren Hemp, Alessia Russo, Georgia Stanway, Niamh Charles, Ellie Roebuck, Esme Morgan) in the semi-finals. 2016 U17 World Cup - Japan (same core as above) knock out England (with added Ella Toone + Lotte Wubben-Woy), before beating Spain in the semi-finals.

It could be argued that England are benefitting from a particularly talented 1998-2000 born cohort (39% of their 2023 squad), supplementing their ‘normal’ level of talent. There’s too much evidence to the contrary to make the same claim about Spain. This is no better illustrated by 15 (eventually 12) regular squad members making themselves unavailable for selection for the 2023 World Cup, with replacements stepping in and Spain finishing as winners anyway. Most notable of these was 1998 born Patri Guijarro, Bonmati’s club and international partner in midfield since 2015, who was singled out as the Best Player at the U19 Euros in 2017 + U20 World Cup in 2018.

With Jorge Vilda’s sacking, many of these 12 players could* be available for selection again, but they are just the tip of the iceberg. There are another 6 squads worth of G+C youth tournament finalists born between 2003-2007 from the last 12 months alone, all looking to squeeze through the top of the funnel, to be recognised as one of the 2 or 3 Spanish footballers in their favoured position. It is the best deepest talent pool the young sport has ever seen and as of yet, there’s no sign of decline or slowing.

*or as things stand the Spanish FA’s decisions could leave them without ANY players available for selection.

That last sentence may seem hyperbolic and understandably, many reflexively assume the USA still maintains an overall talent advantage. Other than participation numbers, there is scant evidence to back up that claim, the only real argument is that because it’s been the case for 32 years, it will continue to be the case. The USA will not slide into irrelevance, they’ll turn up to every World Cup with a chance of winning, but they’re not the presumptive favourites and it’s not because of anything they’ve changed, but the competition improving. They had a huge first mover advantage, but then others started moving - exposing that their talent development system was not as robust or efficient as their senior success suggested.

To get out in front of any “that’s a big claim based purely on a poor finishing performance v Sweden” rebuttals, between 1991-2016 the USWNT played 71 games at the World Cup and Olympics, winning 2.49 points per game, in the last 4 tournaments they’ve won just 1.95ppg and that’s despite going 7 wins for 7 at the 2019 World Cup. In this period, they’ve registered their 2 worst Olympics performances and their worst World Cup performance. Failing to convert a 0.6xG lead over Sweden, doesn’t quite explain the drop in results.

Catarina Macario (99), Naomi Girma (00), Trinity Rodman (02), Sophia Smith (00) and Jaedyn Shaw (04) will form the core of a capable side for the next cycle. Mallory Swanson (nee Pugh) (98) returning from injury will be a big upgrade. Contrasting Swanson’s career with Alyssa Thompson (04), the youngest member of the USWNT squad, is illustrative of how things have changed in the last decade. When Swanson received her first senior call up as a 17 year old to play in the Olympics with a squad who had won the World Cup the previous summer, there was an understanding that her inclusion would have only happened if she could contribute immediately to the best team in the world as a uniquely talented teenager in a global context. Thompson’s inclusions was much more of a training experience, exposure for a player who could be good in the future, but who wouldn’t even rank among the elite teenagers at the tournament when compared to Linda Caicedo (05), Esmee Brugts (03), Aoba Fujino (04), Maika Hamano (04), Melchie Dumornay (03) or Salma Paralluelo (03). In 2022, Thompson was a member of the US U20 side who failed to make it out of their group at the World Cup, and in truth, struggled to make any impact on the games individually. Paralluelo would meet Hamano in another global final between Spain and Japan, Paralluelo scoring two in the final, to win her 2nd World Cup (U17 in 2018), before going on to play a big part in the successful senior campaign just 12 months later.

The US will be hoping that Thompson is impactful on the world stage by the 2027 World Cup, but she won’t just be competing against the aforementioned teenagers from the recent World Cup. 18 months her junior, Vicky Lopez (06) is already featuring for Barcelona, the best club team on the planet, having progressed to 3 G+C youth tournament finals with Spain’s U17 and been named the Best Player at the U17 World Cup. This is not to denigrate Thompson, who is clearly talented, but to highlight how due to increased competition globally, the range of projections you can make for the ‘best’ USWNT teenager’s future have widened significantly in less than a decade.

Does the next Sam Kerr spend 7 years of her career in the US National Women’s Super League? Probably not. That’s a growing problem for US Soccer as the Spanish, French and English leagues grow in financial power and get first dibs on the best talent across the globe, increasingly the overall standard of their leagues that their domestic players have to break through in to - the positive read is iron sharpening iron. Another issue, is the question of if players play too much for the USWNT and not enough club football? Mallory Swanson has already been mentioned, since her debut in 2017 she’s played 89 games in the NWSL - and 88 games for the USWNT. This is common in sports like cricket, the league is built to serve the National team and funding for the league reflects that, but forms a vicious cycle where the National team need to play a lot to keep the sport afloat as the main breadwinners and the league diminishes as their best players aren’t expected to prioritise club football. To contrast Swanson, England’s Georgia Stanway since the beginning of the 2017/18 season, has played 177 club games* and 56 games for England (+ 14 age group games). An over-reliance on friendly games for player minutes is not ideal for player development. but a lot of these games also come in ‘competitive’ CONCACAF competitions. Ultimately, the talent gap is too big for these games to be as useful as they should be - the US have a +206 goal difference (212 scored v 6 conceded) in their 31 year, 44 game CONCACAF Women’s Championship history. This over-reliance on national team game time also causes problems in selection, how do you judge if you have the best 23 players, if the only other sample you see them in is small and often without some of the senior USWNT or elite foreign talent to compare against.

*there’s a very valid argument that European Women’s football has copied their men’s system and are now overplaying the players.

As we’ve previously established, shifts like these rarely have single factor explanations. But if I was to oversimplify it, Spain is a country with a cultural acceptance of a certain style of technical coaching and internal player development but also the accepted recreational style fosters technical skill development. This system helped their mens team dominate G+C senior football for a 4 year period between 2008 and 2012, somewhere around that period female kids were given access to a fraction of the same industrial talent production infrastructure - or as is usually the case, a large enough group of parents and kids seized access, wouldn’t let go and eventually those with control formalised the access. Although Barcelona, the Basque clubs, the Seville based clubs, Rayo Vallecano in the capital and Levante were quick(ish) to pick up on this evolution and formulate their own academies, it was primarily driven from the bottom up, with most players from the first wave staying at community clubs until their early-mid teens. Culturally, it’s normalised for these clubs to focus on technical development as standard, which laid the base for a technically strong player player base who can play 4-3-3 control-ball in their sleep.

The success of the mens team came from applying these technical skills to control football matches in a manner, and with an execution, rarely seen before. This sudden extreme advantage dissipated as an exceptional cohort aged out of their peak and rival nations replicated some things they liked about the system and evolved to counter others. This replication and evolution cycle can happen quicker when you have an established infrastructure and the resources to implement the change necessary. These foundations don’t exist in many nations for men’s football, let alone women’s football, therefore it’s hard to see which nation is primed to counter Spain in the short term. The US reigned as the mass participation first movers, now it’s Spain’s turn as the technical fundamentals first movers.

It’s important to note how recently Spanish football has switched to a structure that is more in line with the men’s system. A fully professional league was implemented in 21/22 and most notably, Real Madrid have finally got involved. The involvement of established men’s clubs in women’s football is not inherently positive, it often comes at the expense of traditional women’s clubs who have put in the hard yards to grow the sport. Real Madrid were originally called Club Deportivo Tacon, before being taken over in 2019, in what can be described as a friendly and welcomed takeover. They almost instantly rose to the top of the sport domestically and will likely remain there as long as football is played. This shift, and wider shift to a development system that more closely replicates the men’s La Liga, is no better demonstrated by the make up of the Spanish U17 World Cup squads from 2014-2022.

2014 U17 World Cup - Barcelona (x5), Atletico Benamiel CF, Atletico Madrid (x2), CA Osasuna, CD Trobajo Del Camino, CE Saint Gabriel, CFF Albacete, FF La Solana, Madrid CFF, Real Betis, Real Sociedad, Sevilla, UD Collerense, UE L’Estartit, Valencia CF.

2022 U17 World Cup - Athletic Club (x4), Atletico Madrid, CD Parquesol, CDE Racing Feminas, FC Barcelona (x5), Madrid CFF (x3), Real Madrid (x5), Valencia CF.

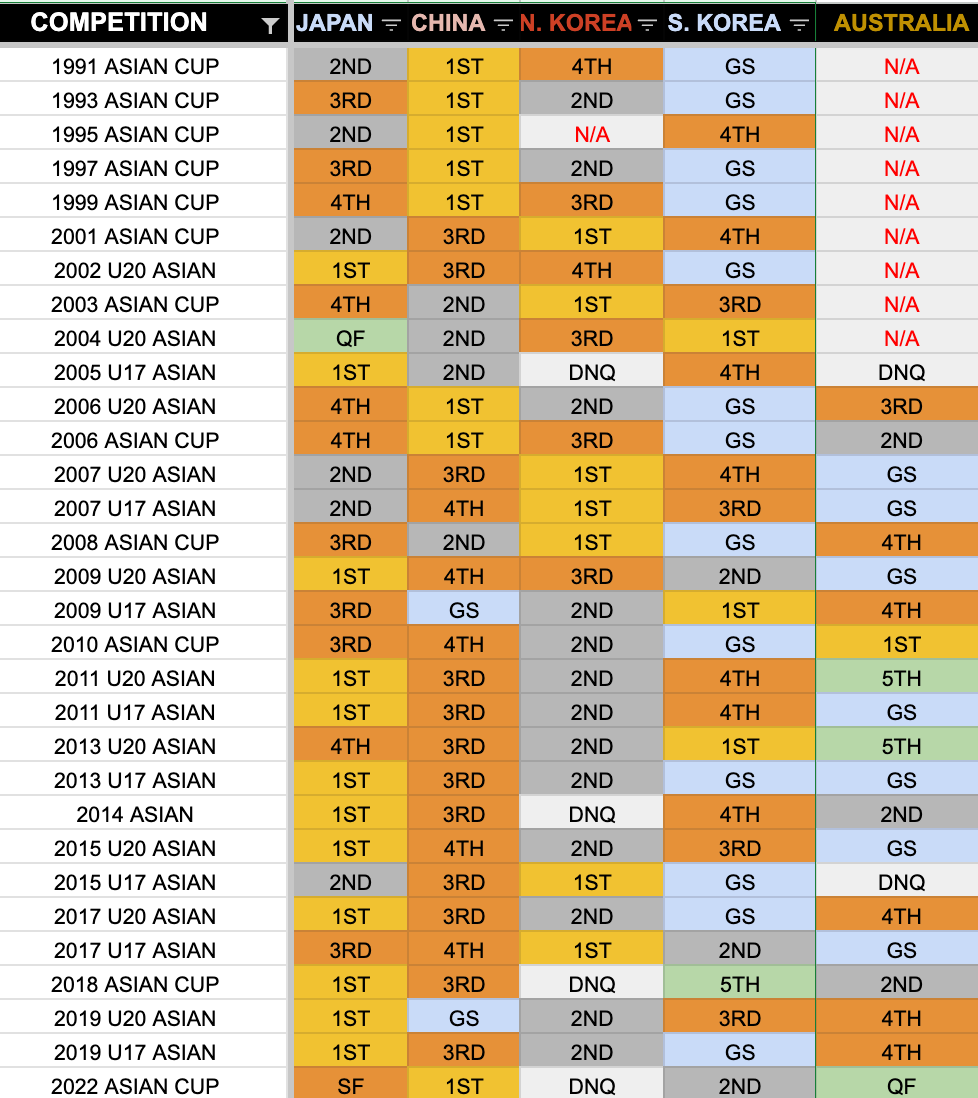

Japan’s football development, is an encouraging case study for any nation hoping to improve. It’s easy to forget that they only qualified for their first men’s World Cup in 1998, despite being an ever present since, having only created a professional domestic league in 1991. Technical proficiency, control of games without needing the ball and effective transitions - there are very few nations in the modern era who have simultaneously built a coherent football culture, developed a style of play and produced a depth of talent on a scale that rivals the Japanese. Rarer still, is a nation who has developed this in both men’s and women’s football. Perhaps, due to the lower barriers to entry, this development has lead to more obvious success in Women’s football - most notably as the 2011 Women’s World Cup winners and the 2015 runners-up. Although, they already reached the peak of the sport in 2011, I think the decade since has shown even more concrete signs of Japan’s sustainability as a force in women’s football. Qualifying for four of the last five U20 World Cup’s and ending up twice in 3rd place, once as runners-up and champions in 2018. The launch of their domestic professional league only happened in 2021, which suggests there’s still huge scope to grow and develop from this point on.

It’s probably important to discuss at some point, what the U20 Women’s World Cup is and what it isn’t. It is not a competition between the best U20 teams in the world. It is a competition between the U20 teams who qualify in accordance to the structure that FIFA have designed. One of the reasons why both the female and male versions of the U20 World Cup, can be so refreshing, is that they do not weight qualification places towards the European nations as heavily as the senior version. For example, the 2022 version was a 16 team tournament held in Costa Rica, who therefore took a spot as the host nation. The other 15 spots were divided as such - 3 spots to Asia (Japan, South Korea, Australia*), 2 spots to Africa (Ghana + Nigeria), 3 spots to North America (Canada, Mexico, USA), 2 spots to South America (Brazil + Colombia), 1 spot to Oceania (New Zealand) and 4 spots to Europe (France, Germany, Netherlands + Spain). Not all confederations are currently at the same stage of their development or investment in women’s football, therefore, the ease of qualifying has not always been equal across the board.

If we’re judging teams based on their U20 World Cup performances, we need to accept that it’s easier for Japan to get to the tournament, than it is for European teams to qualify. In fact, quite often it’s harder for a European team to qualify for the U19 Euros, that acts as qualification for the U20 World Cup, than it is for Japan to qualify for the World Cup itself. This is countered slightly when the draw for the World Cup itself is made - because of their historic results and the fact they often qualify as Asian Champions - Japan traditionally are a no.1 seed. In most other competitions this seeding would be beneficial, but in the U20s; 1) the host (in recent years Costa Rica + Papa New Guinea, who wouldn’t have qualified themselves but will never host a senior tournament) also earn a no.1 seed and 2) you are not able to be drawn against a nation from your own confederation. This takes some of the weaker teams out of Japan’s scope for the draw, but also guarantees they have to play a European team - this concoction has lead to this spread of group stage opposition in the last three editions - Spain (x2), USA (x2), Netherlands (x1), Ghana (x1), Paraguay (x1), Nigeria (x1), Canada (x1). In the knock-outs, they have then faced - Spain (x2), Brazil (x2), France (x2), USA (x1), Germany (x1), England (x1). You only need to be a casual follower of women’s football to see the strength of that schedule, 3 losses to Spain (we covered them earlier) and a single loss to France are the only games Japan haven’t won from that 18 game slate.

We’ve established that Japan are Spain’s perennial rivals, facing each other 8 times in the last 7 age group World Cups, and likely to face off countless times again in the next decade. Which is the 3rd country, after Japan and Spain, to win both the U17 and U20 World Cup? Japan’s continental rival, North Korea. Of all the variables impacting the women’s football landscape that i’ve tried to touch on, they’re the most complicated. Over the last 15 years, they may lay claim to being the most successful youth system in women’s football, with 4 U17 World Cup finals (3 wins) and 2 U20 World Cup finals (1 win). In 2011, their senior team had a raft of positive doping tests at the World Cup, were banned from subsequent competitions and only returns, for a failed run at Asian Cup qualifying in 2017. During this time, their youth teams continued to compete, despite graduates having nowhere to graduate to, finishing 2nd at worst in all continental tournaments all the way up until 2019. In November 2019, North Korea men’s senior team played a World Cup qualifier against Lebanon, this was the last time a side representing their nation took to the field at any level of football on either the men’s or women’s side. Having withdrawn from every fixture or tournament since, a return in the 2023 Asian Games is expected, to end their 4 year absence. On the women’s side, if they do not return, then their wins, finals and World Cup qualifications, will have to trickle down to other nations, the likely recipients being China, South Korea and Australia. You can not win, if you do not play, and currently North Korea are not playing.

For as cynical as you can be about North Korea’s youth results and the rumours of age doping or drug doping, their continued absence is a shame for a nation who did seem to have a longstanding interest in women’s football. So much so, that in 2010 ‘Bend it Like Beckham’ or at least an edited version, became the first western movie to be shown on North Korean television. I’m not saying the 2016 U17 World Cup and U20 World Cup double win was directly caused by Parminder Nagra, but i’m not not saying it.

*Asian women’s football shines a light on how random factors can alter the development of a nation’s football system. Who is the 6th best Asian football nation?It’s a trick question really because Australia isn’t in Asia, yet they occupy one of the top 5 spots and may be established as the 2nd best side. This all hinges on their 2006 decision, to leave the Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) and join the Asian Football Confederation (AFC), a decision made to play against more competitive (and richer) opponents for their own personal development. Not only did this make it much harder for Chinese Taipei to ever make a semi-final again (they made 9 of the first 12 Asian Cup SFs) but it also opened up space for New Zealand to win every single Oceania Championship (15 out of 15) at U17/U20/Senior level and to qualify for every World Cup at every age group since. The main driver of New Zealand becoming the most consistently successful team on the planet, was completely out of their control, and at the expense of their most competitive and financially lucrative rivalry.

I’d recommend keeping an eye out on what happens in the future - the men’s World Cup will expand to 46 teams in 2026 - to do this they will increase the amount of teams qualifying from every confederation. There will be a guaranteed 8 (+ 1 play-off chance) spots for Asian teams and for the first time, a guaranteed entrant (+ 1 play-off chance) from Oceania. As things stand, both New Zealand and Australia will likely qualify through the new allocation, but there is a chance for both teams to see the value in moving confederations. Australia, because they now have the guarantee of a WC spot through their ‘home’ system, something which they did not have when they decided to leave in 2006. New Zealand, because they’d gamble on their chances of being in the top 8 Asian teams, at the expense of a guaranteed World Cup spot - for the same development and financial reasons that Australia did in 2006. Or there’s an argument that AFC members, especially nations targeting growth like India, Qatar and China will push for Australia to return to the OFC to increase their chances of World Cup qualification? Or FIFA could push for Australia to return to the OFC as it’s currently the smallest confederation and needs their presence to have any chance of growing? Or Russia* could join the AFC and suddenly the odds on World Cup qualification via Asia become less desirable for the Oceanic nations? Or could the OFC and AFC be formally combined and FIFA simply be made up of one less confederation? If New Zealand did decide to try and switch, I suspect we’d see the latter, it’d be the end of the OFC as a standalone, potentially for the better of all involved. The knock on effects of any of these changes would be huge - Tahiti, Solomon Islands or Papa New Guinea could be heading to the World Cup - but this is just the perspective from the men’s side of football. There are currently no plans to expand the Women’s World Cup and therefore any move would jeopardise the current status quo and ease of qualifying that New Zealand’s women now enjoy. Football, it’s not always down to what happens on the pitch.

*The Champions League riches are the modern anchor tying Russia to UEFA, with huge Saudi and Qatari investment in their leading clubs, the Asian Champions League just got a lot more attractive.

England are the great unknown among Spain’s current rivals, the reigning European Champions and World Cup runners-up, on a run of 5 successful senior tournaments in a row, yet the success was built on a system that has been overhauled and replaced in the last decade. The tireless work of a lot of passionate individuals in the 1990s and early 00s, rather than a coherent system, is responsible for the current England team. No story is exactly the same, but many of the 22/23 squad share certain characteristics on how they got into the sport - an enthusiastic parent who encourages them to play for a boys team in primary school, an enthusiastic parent in their community who is willing to create and run a girls team from scratch to give their child some place to play, that girl dragging her friendship group from school into the sport so they can field a team, a teacher who is willing to run a girls football team off their own back, lucking into growing up in one of the rare areas with an established girls club (often attached to long established community mens clubs in former mining towns) run by keen volunteers. This reliance on individuals is admirable, but creates a delicate eco-system with only a small pool of players, the existence of whole age groups in major cities sometimes hinging on the continued involvement of a single parent or a child. One quirk of this lack of widespread infrastructure is the development of hyper-localised pockets of players - Jill Scott, Steph Houghton and Demi Stokes all playing for Boldon Community Girls Club or Lucy Bronze and Lucy Staniforth attending the same school and playing for Blyth Town. If you displayed talent in this first stage of your development, you’d have to hope you lived near one of the 20 Centres of Excellences (that then grew to 52, before retracting to 28 regional talent centres by 2022) or more likely that you lived within commuting distance and had a willing designated driver. If you were even luckier than that, you might live near one of the few in-house academies attached to WSL teams, and have access to more regular coaching, from an earlier age alongside a more challenging games schedule.

The next era of English women’s football will be the industrialisation of talent development, away from the individual, towards the systematically mass produced. This had begun but was accelerated by the full professionalisation of the Women’s Super League (WSL) in 2018, with one of many conditions of entry being the operation of an academy team. This evolution was compounded by the concurrent financial power of the Premier League - government requirements for them to contribute to women’s football and the fact that their members can dwarf the spend of European rivals by assigning a rounding error of their weekly spend to their women’s team. The reason for this increased (relative, can still be much more) financial push behind women’s football, is also fairly simple. The England women’s team have been very enjoyable to watch on free to air television* for the last 15 years, their popularity is now undeniable across all demographics and even those who aren’t invested in the idea of equality, are invested in the idea of ‘this thing could make us a lot of money if we get in early.’

*Women’s football is so popular in the UK now, that it will be a a missed opportunity for women’s sport if the BBC does broadcast Great Britain’s games in the 2024 Olympics (should they qualify). Due to rights sharing with Discovery, the BBC no longer has complete control of Olympics broadcasting in the UK. As part of this agreement, the BBC is limited to 350 hours of live coverage and only two live streams at once. Unlike most Olympic events, football does not have the regular gaps to allow for coverage to break to show other things, once you commit to showing a game, you’re locked in for nearly 2 hours. GB’s games would be the highest rated TV events of the whole Olympics, perhaps only matched if Andy Murray was to make a run to the Olympic final (argument for tennis not being shown is even stronger than football). 350 hours sounds like a lot, but when you add Athletics, Cycling, Gymnastics + Swimming, it quickly diminishes over a month. The advantage these sports have are the natural breaks in play, and a variety of different events in quick succession with many different athletes competing. The BBC now have an editorial decision to make, to chase the ratings for potentially 12 hours of uninterrupted coverage or to give minority sports the air time, at their showpiece event. A strange flip for women’s football, considering how helpful the televised Olympic games were in their growth. The BBC’s moral sacrifice, would be Discovery+’s gain, who would see a bump in subscribers tuning in to watch Great Britain’s most popular team.

The FA are not solely relying on clubs deciding to fund their own academies more robustly, at the regional level 23/24 will see the implementation of the 67th Emerging Talent Centre (ETC). The ETC’s are part of the new player pathway that began to roll out in July 2022, to replace the existing Regional Talent Centres (RTC). The capacity to receive regular high level coaching will increase from 1,722 players to 4,200 and the geographical targeting should ensure that 95% of the population is within an hour of one of these centres. A category system is also being introduced into the club affiliated WSL academies, to drive standards and ensure minimum requirements of coaching are met, for the 14-20 age group in particular.

These changes can’t be judged this decade, but the theory is to increase contact time for players with dedicated coaches and to have more systematic approach to moving players towards the skinny end of the talent development funnel. One casualty of the professionalism of the WSL has been women’s football in the North East, with none of their teams receiving original licences to play in the top tier when the WSL was created in 2010 - Sunderland most impacted, having to drop down from the top tier, despite just finishing 5th. Despite producing 7 members of England’s 22/23 Euros + WC squad, the North East currently have no representative teams in the WSL and therefore lose a lot of homegrown talent prematurely to teams further south, which makes it harder for them to earn promotion, therefore they lose a lot of talent prematurely to teams further south and so on and so on. The inability to retain talent and grow, also impacts further investment in their own academy, which could potentially deny a whole region the same opportunities as others. 11 of the 22 current WSL + Women’s Championship teams are based in the South East, 5 are based in the North West and 6 cover the rest of the country, this geographical disparity is limiting to the growth of the sport. Rugby Union’s Premiership should serve as a warning to the WSL about what happens if you neglect certain regions and overcrowd others with teams - eventually there’s only so many people to support each team in London and growth stalls. Newcastle’s takeover and subsequent investment may solve a problem for the FA, but other regions may not receive such ‘generous’ outside subsidies.

The macro impact of these reforms and increased investment should equal more players and better players, but it will be interesting to see where these players come from and how this changes in the future. England used 27 players in the most recent U17 cycle, 15 of those were called up from Arsenal or Chelsea - an abnormal spread for England and more in line with Spain’s Barcelona and Real Madrid player split. It’s one age group, in one cycle, but these are the two teams with resources to move earliest to increase academy spending and recruitment. 15 of 27 may be an extreme outlier, but could be indicative of the new norm, until the rest of the WSL closes the spending gap. If the ‘elite’ player pool is to become less diverse by club origin, the FA hope their reforms will result in an overdue shift in the racial diversity in women’s football from the England senior team to the earliest amateur age groups. Is the player pool becoming more diverse anyway? Yes. Will these reforms help? Probably, more of the country should have access to coaching and clubs are increasingly incentivized to find talent. Are they a silver bullet? I’m unconvinced. On the men’s and women’s side of the game, I think success at the elite level covers up the lack of easy access to facilities, access to coaching, and most overlooked - access to time for participation. This applies to almost every demographic in the country and we’ve been conditioned to ignore the easiest and most egalitarian way to solve this, state school sports and free access to local facilities.

A lot of ideas in talent development are focused on the players who survive in the sport to get identified or flagged as talented and therefore make their way into the funnel in the first place. General participation, can often be overlooked. It’s not that investment isn’t being made on the ground level - the facilities and pitches in England have never been of a higher standard - but what about real access to this investment? The true key to participation is to build an environment that encourages passive participation in sport, in this case football. What does that look like in practice? Effectively, remove as many obstacles to participation as possible and get people playing without it having to be a conscious choice or something to be planned. Think back to how you participated in sport when you were younger, for most people the vast majority of the hours they spent playing was not in an organised setting. Whether that be on a local street or green space, a garden, or at school on the concrete/grass surface. What happens when financially strapped local councils continue to sell off their open space to developers for housing, who then build tetris designed estates, maximised for units to sell and not recreation? Primarily, less places for children to play when at home. Secondarily, this puts more pressure on the under-funded local schools to cater for the bigger population. What does a school do when they need more classroom space? They build on what was previously a recreational area for kids at lunch or on breaks (let alone PE), this reduced space is then required to be used by more children at the same time and the first rule usually implemented in this scenario is simple - no ball sports allowed. Maybe this increased pressure on schools leads to a bigger, new state of the art school being built, bigger class-rooms, better equipment and best of all, a gym, modern 4g pitches and grass pitches with proper drainage systems. Better facilities for the local community, with no obvious downsides. The financial argument to justify this investment, is that these new pitches and facilities would have to be rented out at every available opportunity to local clubs and teams, to bring in steady income. The facilities get used, the school makes a tiny bit of money, the local teams get better pitches and the council now has an opportunity to make a bit more money by selling the land where the old pitches were based. The problem is that these old pitches didn’t have a 13ft fence surrounding them and a security guard manning the single entrance. I think it’d be eye opening for a lot of people to go back to look at the places where they grew up playing football, not just the organized paid football, but the unstructured football that you have probably forget you even participated in, to see the changes in environment and infrastructure that’s taken place. No doubt, the facilities have improved, but how many are truly accessible with just a ball and no wallet, how much of the access is for children to take and not just to be given.

As the WSL grows in financial power, the coaching standard rises, and the product continues to establish itself as the best league in the world, there may be less reasons for English players to leave. 5 members of the 2023 World Cup squad decided to move to the US as teenagers to play in the NCAA system, that pathway could become extinct in the next generation, as the resources now exist for English clubs to offer the elite talent competitive professional contracts at the age of 17. This increased financial leverage may not always benefit English talent, as clubs can increasingly attract the best talent from abroad wile simultaneously hoarding more domestic players on pro contracts. The glorification of transfer fees in women’s football has already begun, the time has already passed, but it felt like a missed opportunity for the sport to embrace a different form of transfer system rather than tying up resources copying the unsustainable and inefficient model that the men’s game has been absorbed by.

24/25 should see yet another huge shift in the English women’s game, with as of yet unconfirmed widespread structural changes set to take place in line with a new TV deal. The main change, is away from FA governance and towards the same model as the Premier League, with a new company owning and governing the top two tiers itself in order to establish the greatest/most profitable women’s league in the world. More resources for talent development, potentially, but this is unlikely to have only positive connotations for the England women’s team and is short on any specific details right now. All you can guarantee, is that the talent development system producing players is completely different to the one that produced the 1987-2001 born ‘Golden Generation’.

Toni Kroos was born in Greifswald, East Germany in January 1990. Soviet-occupied East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic, was reunited with West Germany on October 3, 1990. Toni Kroos is one of the greatest German footballers of all-time, a child prodigy named the 2007 U17 World Cup Golden Ball winner and a key player in their 2014 World Cup winning senior side. East Germany, accounting for 15% of Germany’s population, has barely produced a national team standard player born since Kroos.

Freddie Tuilagi moved to England from Samoa in the 1990s to play Rugby league. He moved to Cardiff in 2004 to play Rugby Union before moving to France later that year. His younger brother Alesana Tuilagi made the move to England to play Rugby Union for Leicester Tigers in 2004. Freddie + Alesana’s younger brother Manu, who had lived with Freddie in Cardiff, remained in Leicester with Alesana. Another Tuilagi brother, Henry, also moved to Leicester in 2004 before moving to France in 2007, with his son Posolo. Feʻao Vunipola moved to Wales from Tonga in the 1990s to play Rugby Union. He brought his sons, Mako and Billy, with him before settling across the border in Gloucester after he retired. Kuli Faletau moved to Wales from Tonga in the 1990s to play Rugby Union, he brought his son Taulupe with him. Manu, Mako and Billy all started the 2019 Rugby World Cup Final for England and have played a combined 193 test matches for England over the last 11 years. Posolo won the 2023 U20 Rugby World Cup as a starter for France. Taulupe Faletau has played 103 test matches for Wales over the last 12 years.

Filippo Inzaghi (born 1973) is the top scoring Italian in the history of the Champions League, with 46 goals. Alessandro Del Piero (1974) is 2nd with 42 goals, Marco Simone (1969) 3rd with 23 goals and Francesco Totti (1976) in 4th with 17 goals. Alberto Gilardino (1982) is the top scoring Italian in Champions League football born since 1976 (Totti). Italy won the World Cup in 2006, with a squad containing Inzaghi, Del Piero, Totti and Gilardino. No Italian born since 1982 has scored more Champions League goals than Gilardino, Lorenzo Insigne (1990) coming closest by tying on 11 goals. Italy were knocked out in group stage of the 2010 and 2014 World Cup and didn’t qualify for the 2018 or 2022 editions.

By 2006, there were 16,425 resident Nigerians in Ireland. In 2003, Emeka Onwubiko became the first Irish-Nigerian to represent the country in football, playing for the U15s. In 2003, the Irish Supreme Court ruled to remove the automatic right to permanent residence for non-Irish national parents of Irish-born children. A 2004 citizens referendum, voted to revoke an Irish-born child's automatic right to citizenship when the parents are not Irish nationals. By 2016, there were 6,084 resident Nigerians in Ireland. In 2023, Rhasidat Adeleke (born Dublin 2002) broke the Irish women’s record for 200m, 400m and came 4th in the 400m at the World Athletics Championships. In September 2023, 11 of the 45 players called up by Ireland at senior and U21 level were Irish-Nigerian.

The takeaway from this shouldn’t be that i’ve given answers, solutions or even airtight future projections about any of these topics. It should just make you think about the questions we don’t ask and the variables we ignore when we discuss talent development or success. What do the four bullet points above make you think? How do they impact your projections for the next decade of 6 Nations Rugby? How do they make you reflect on the last decade? What new questions do they make you ask about other sports, other nations, other topics?

It’s understandable to try to boil down a nations sporting performance into an easily digestible narrative, usually that narrative is massaged by the governing body in charge, history is written by the victors (J.S). A focus on the controllables and the changes these organisations have or haven’t made is a good starting point. Underestimating or completely ignoring outside variables make it impossible to judge the impact these changes had or to then make projections for the future. You’ll never be able to consider them all (you’ll barely be able to accurately measure any) and each new one you do consider, will open the door to five more, but it’s a worthwhile Sisyphean task. After all, “you can not win, if you do not play.”